Club Meeting: 16 March 2022

Report by Denise Donovan

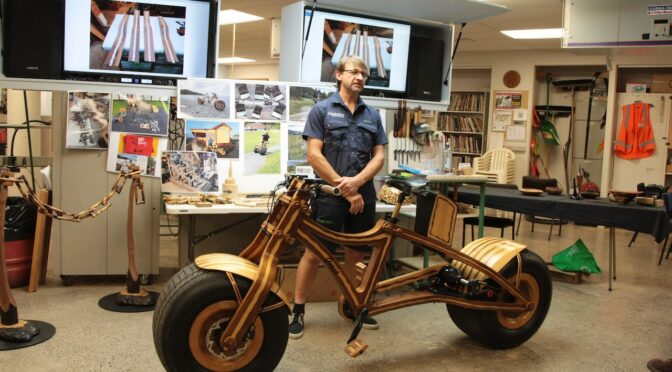

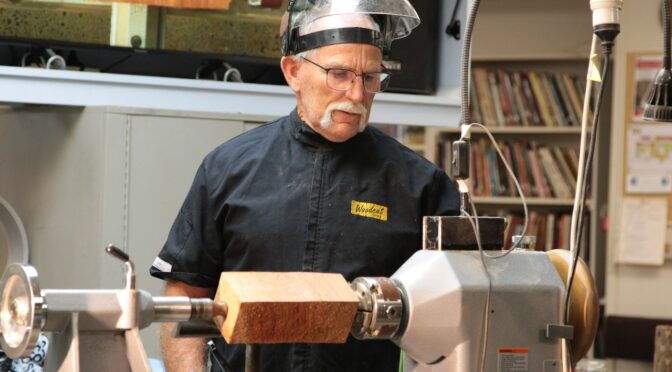

On Wednesday we had a visit from Daniel Strekier of Masterpiece Woodworks, a passionate woodworker, with an eye for a challenge.

Weighing in at 60kg, with a top speed of 47.2 km, let me introduce Grace, the result of a year of hard work (6 months if you don’t count breaks, which I’m sure were much needed). Grace has over 500km of trail riding tucked under her tidy seat, with many more to come.

This bike is a woodworker’s dream, featuring amazing laminations of Walnut, Ash and American White Oak, a hollow wooden frame, 22 speed derailer system, hydraulic brakes, and the fattest tubeless tyres you ever saw on a bike.

Each wooden piece on this bike has been lovingly handcrafted by Daniel himself, through trial and error, a wealth of woodworking knowledge, and an “anything is possible” attitude.

Daniel originally started the bike by accident, basing its’ design around 2 tyres he purchased for a remote-control gate that never quite happened, instead deciding he needed a challenge, and a project that displayed his talents to current and future customers.

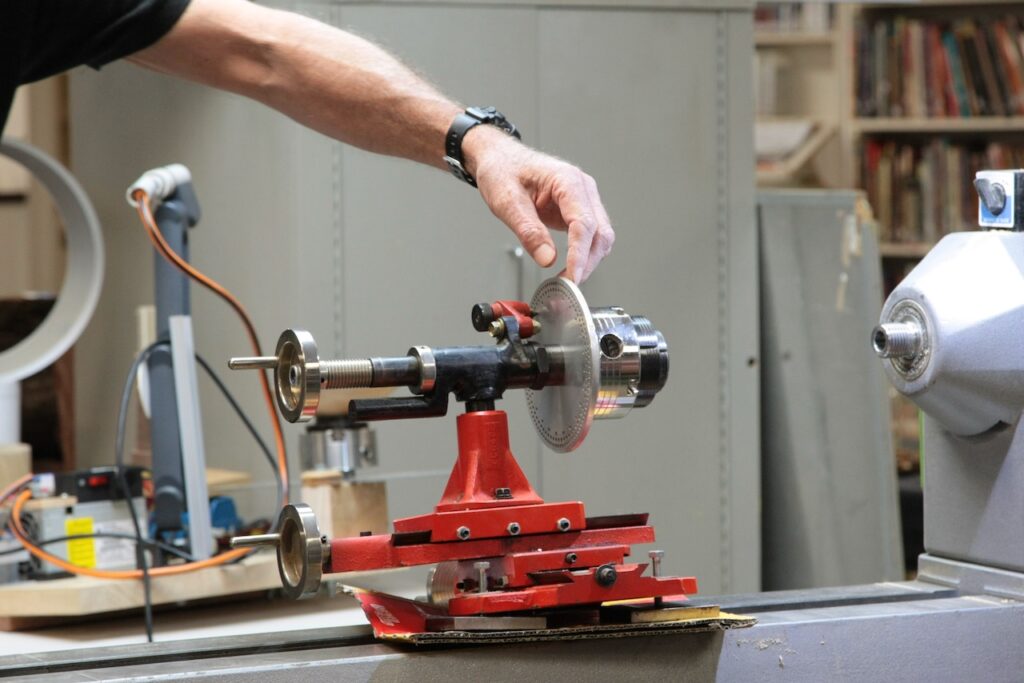

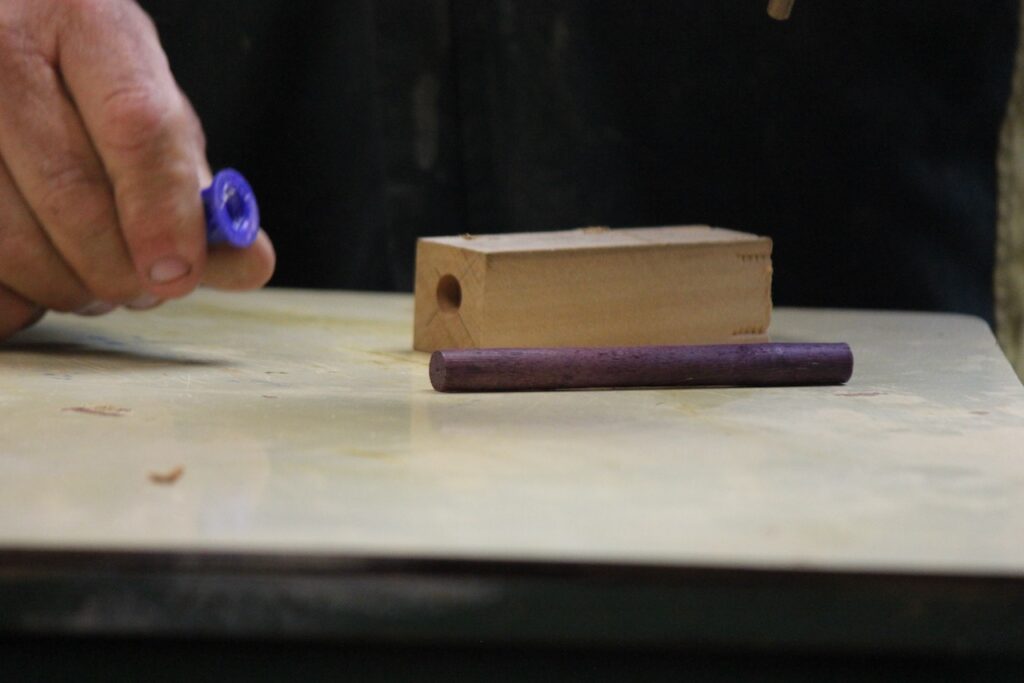

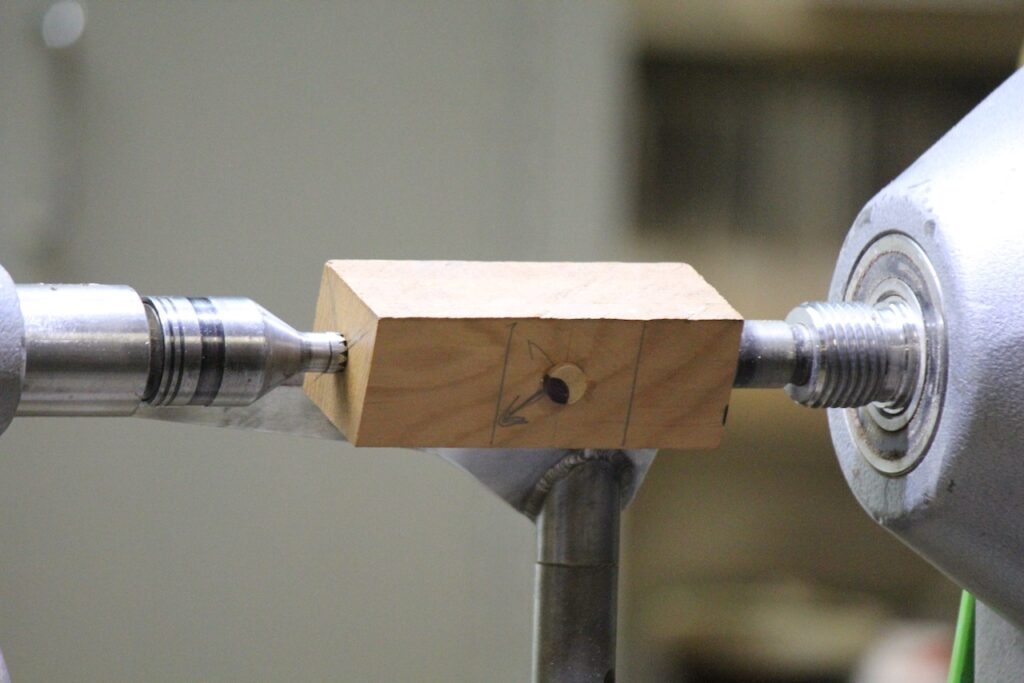

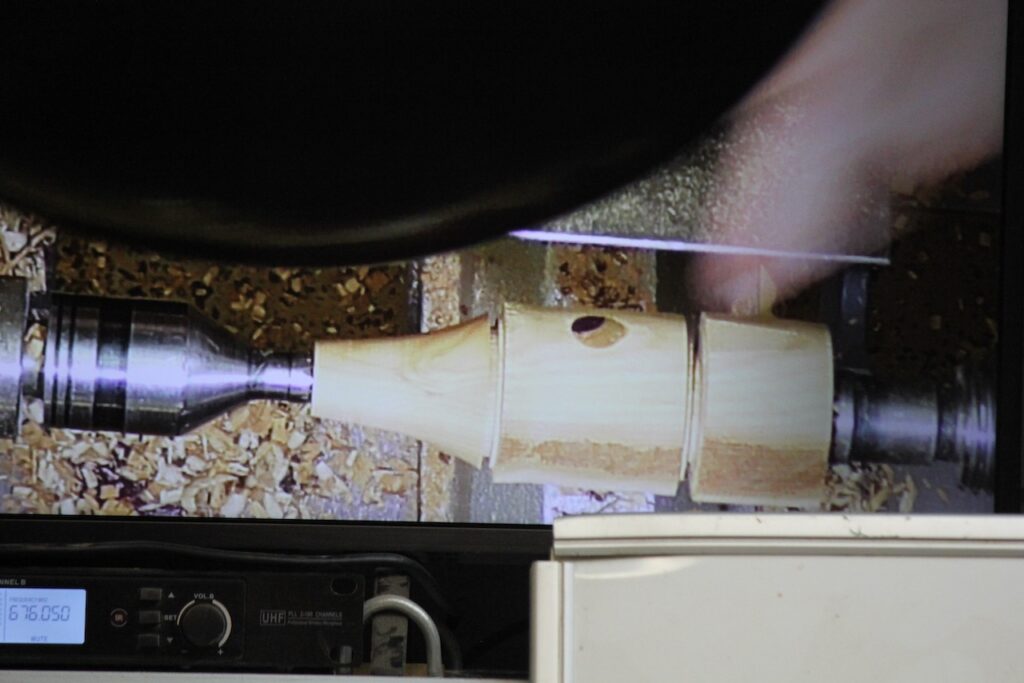

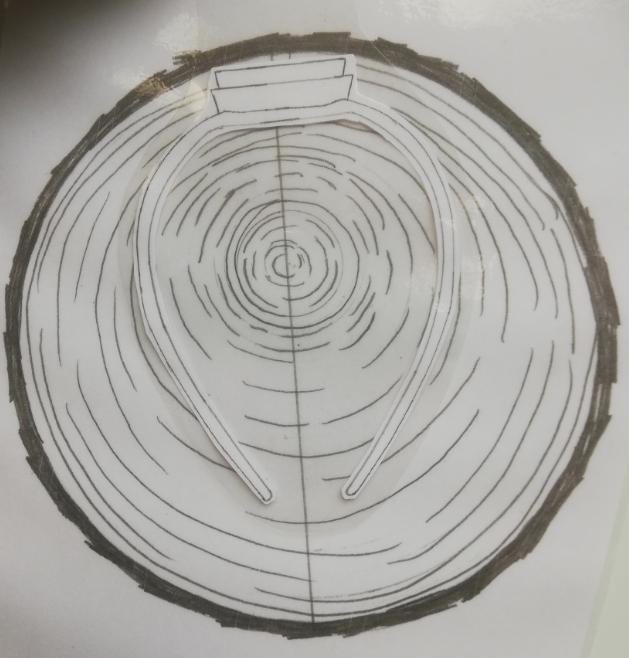

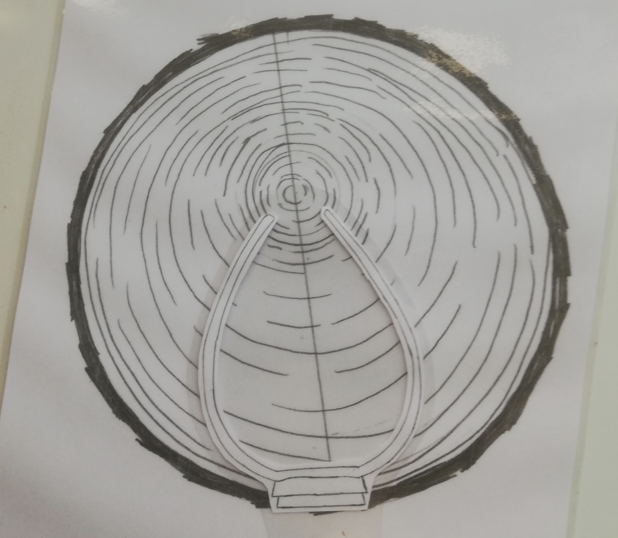

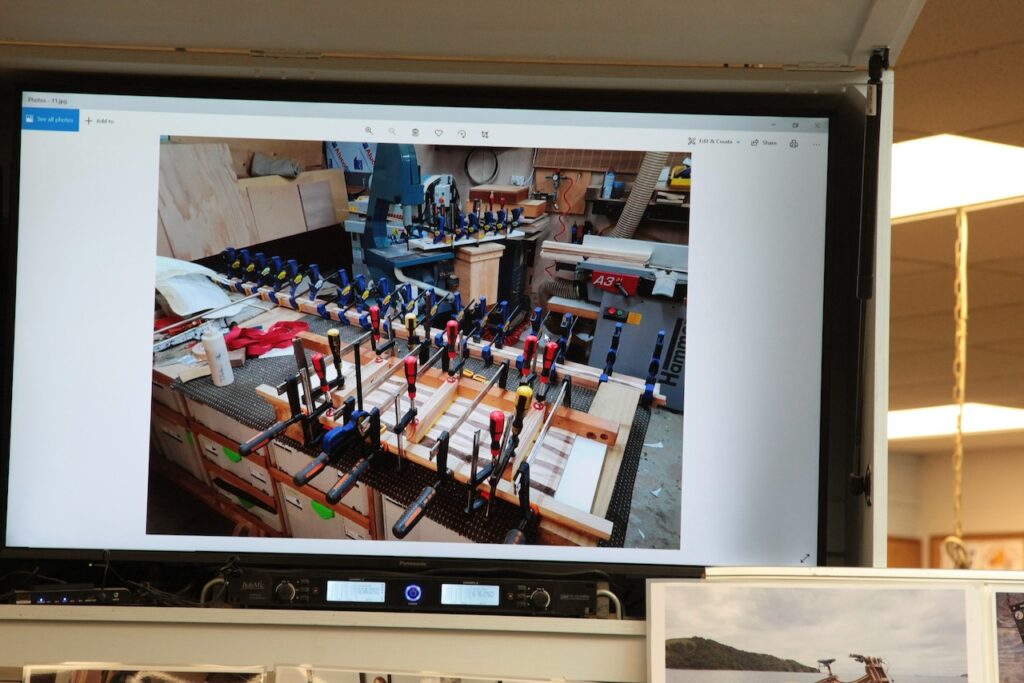

The 17.5 kg tyres and rims were started with a plywood wheelbase, and white oak rims with finger joins. The mudguards were a 2-way lamination using three 2mm sheets which provided quite a challenge, using a stave process popular in barrel design and hot water to shape the brackets. They were then strengthened with an epoxy fiberglass underlayer. The solid forks were each assembled from 9 pieces of wood, with a steamer utilised to bend each individual layer.

The frame design of the bike took 4 hours alone. Assembly of the 8kg framed consists of a basic MDF frame designed around a mountain bike. The original design also used a normal gear system but was later changed to a Shimano 11 x 2 gear hub. As “straight lines are too easy”, the unique lamination was done by cutting and gluing 2mm strips, creating curved lines by cutting several strips together on a band saw, and then mixing them up.

Not everything could be wood, so improvisations were made where strength was a factor … the handlebars and chain guard encompasses carbon fibre, the wheel axels are steel, and the pedals are aluminium wrapped in wood

As if the bike wasn’t enough, Daniel has also made his own matching helmet using resin and wood cut with a plug cutter, and a stunning wooden chain and functional wooden lock

All this was completed over a 12-month time frame, with many hours just standing and staring while thinking over the technicalities, many sleepless nights, while also building a business.

In the words of Daniel … “You can do anything you want if you want it enough”

Grace of God was so named as it translates to “Thank you God for the possibility and Capacity”

Keep a lookout for Daniel’s next project – a wooden e-bike